In 2023, it would not be far-fetched to proclaim that the traditional 9-to-5, in which employees clock in at 9 am and out at 5 pm, with a one-hour lunch break in the middle, is dead.

Indeed, a large part of the 21st-century active population may be found either working from home, freelancing for several clients – possibly even as a digital nomad – or, on the lower rungs of society, taking their orders from the algorithms of an Uber-type food-delivery platform.

While work has always evolved, its recent transformation has taken place at an unprecedented speed and affected the workforce to an unprecedented extent. As we explained in an article on ‘new ways of working’ published in The International Journal of Human Resource Management, modern work arrangements challenge existing notions about where work takes place, how it is done, who does it and even what work is. The Covid-19 pandemic accelerated existing trends, suggesting that an increasing number of individuals carry out work in a non-traditional way.

So, when can work be described as ‘new’ as opposed to ‘old’ ways of working? Remote work is one obvious aspect. While the past couple of decades saw a significant increase in homeworking (up 115% in the US over the 2005-2015 period, for example), the Covid-19 crisis made it relevant to a majority of the workforce nearly overnight. Automation is another aspect, with estimates suggesting that in about 60% of occupations, one-third of tasks could be automated. Last, but not least, the number of gig workers – on temporary or freelance arrangements – is projected to rise to 78 million in 2023, up from 43 million in 2018.

These are not minor adaptations, but large-scale transformations. Yet little is known about their impact on employee experience. This is why we set out to explore four major transformative processes and their benefits and downsides for employees’ attitudes, performance, skills, career advancement and well-being.

1. Workspace and time

Flexible working, usually in the form of remote work, is generally perceived as beneficial for employees. Numerous studies show that they enjoy increased autonomy in managing their schedule and tend to report greater levels of satisfaction than their office-based counterparts, with such positive outcomes as reduced stress (no more commuting) and fewer work-life conflicts.

But, recent studies also show that ‘high-intensity teleworkers’ struggle over disconnecting outside working hours, which induces stress and exhaustion, with higher intentions to quit. While ‘telepresence robots’ (screens enabling co-workers to see each other) have been studied as a way to decrease feelings of isolation, they are also potential threats to privacy.

2. Work relations

The employment contract, once the basic foundation that ties individuals to an organization, in the words of the researchers, is waning. Instead, employment relations are now (more loosely) organized along such options as temp agency workers, freelancers, contractors, etc. This whole ‘gig economy’ has grown to the extent that crowd work represents the main job for 2% of the entire workforce in 14 countries in Europe. Gig jobs also include direct sales and the so-called ‘sharing economy’ where platforms digitally connect workers.

Discussions around gig jobs emphasise their positive aspects, such as schedule flexibility and higher levels of compensation (the latter evidenced by a 2019 study comparing Uber drivers with traditional taxis). Gig workers, however, often hold ‘precarious positions’ and lack social and job security compared to ‘regular’ employees. Plus, in a bid to appear continually available, freelancers tend to work irregular hours and their work is often in conflict with their private commitments. Although they may perceive their careers as successful, these are uncertain and fluid and without some level of organizational support, freelancers have limited chances to develop their skills.

Finally, for those being assigned tasks through the algorithms often embedded in the digital platforms of the sharing economy, the lack of human interaction and feeling of surveillance can result in reduced well-being.

3. Content of work

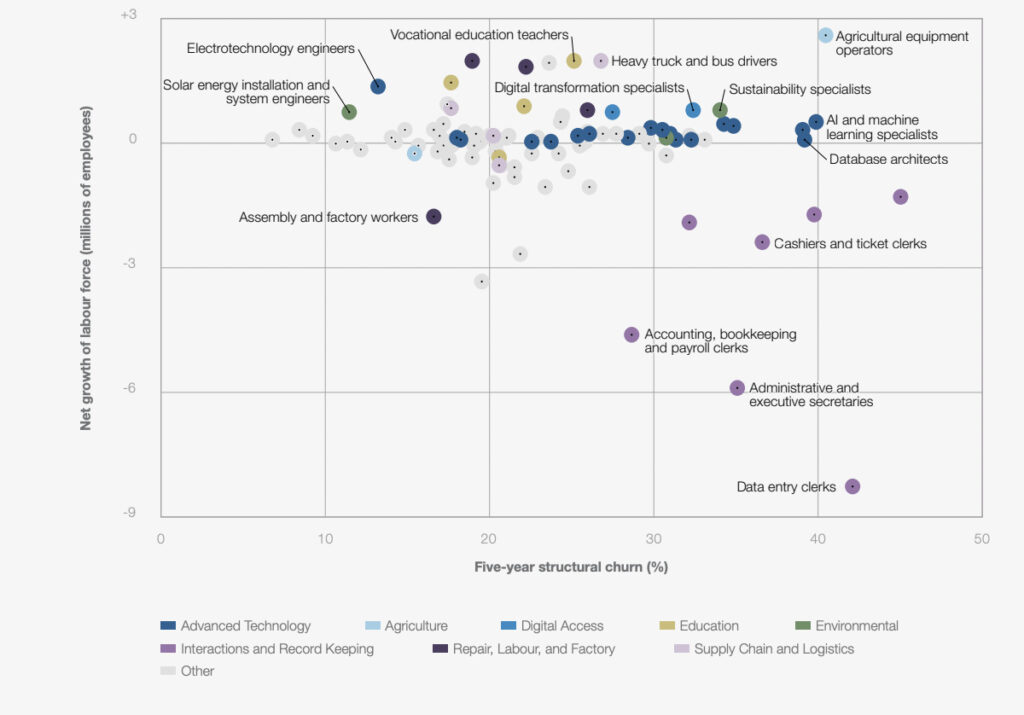

Much ink has been poured about technology automating tasks previously carried out by humans, particularly dangerous or repetitive tasks, and about the fear – still very much alive – that jobs will simply disappear, with consequences in terms of anxiety for workers, especially among the less skilled.

More recently, research may have shown that machines may unleash human capabilities, but has also sparked questions about issues of agency that may arise for those working alongside ‘smart’ machines, with possible surveillance issues and broader questions about new relations of power, authority and identity.

4. Allocation and organization of work

Conventional management hierarchies are evolving towards more agile, participative ways of working. Agility is presented as a mainly positive new way to allocate work for employees, with improved engagement and satisfaction. The increased autonomy given to teams helps them navigate uncertain environments and contributes to the psychological empowerment and motivation of agile teams, with positive implications for the team’s innovative behaviour and project performance.

One caveat is that when management is delegated to algorithms in digital platforms, empathy and human connection are lost.

Challenges for human resources

Given the increase in non-traditional ways of working, HR practices need to adapt. For instance, HR practices that are less often included in traditional HR bundles, such as well-being programmes or practices promoting job security, might be of high relevance to workers who are at the periphery of organizations (e.g. temporary or agency workers).

Regarding flexibility, they must consider how to align the demands of workers (many of whom are less than keen to return to the office) and the operational needs of managers (persons present on-site to train new recruits, for instance). HR professionals will need to develop sophisticated solutions to all of these challenges.

This article was originally published by the World Economic Forum.

Authors

Kerstin Alfes

Professor and Chair of Organisation and Human Resource Management, ESCP Business School (Berlin campus)

Argyro Avgoustaki

Professor of Management, ESCP Business School

Alexandra Beauregard

Professor of Organizational Psychology, Birkbeck College, University of London

Almudena Cañibano

Associate Professor in Human Resource Management, ESCP Business School, Madrid Campus

Maral Muratbekova-Touron

Professor of Management, ESCP Business School

License and Republishing

The Choice - Republishing rules

We publish under a Creative Commons license with the following characteristics Attribution/Sharealike.

- You may not make any changes to the articles published on our site, except for dates, locations (according to the news, if necessary), and your editorial policy. The content must be reproduced and represented by the licensee as published by The Choice, without any cuts, additions, insertions, reductions, alterations or any other modifications.If changes are planned in the text, they must be made in agreement with the author before publication.

- Please make sure to cite the authors of the articles, ideally at the beginning of your republication.

- It is mandatory to cite The Choice and include a link to its homepage or the URL of thearticle. Insertion of The Choice’s logo is highly recommended.

- The sale of our articles in a separate way, in their entirety or in extracts, is not allowed , but you can publish them on pages including advertisements.

- Please request permission before republishing any of the images or pictures contained in our articles. Some of them are not available for republishing without authorization and payment. Please check the terms available in the image caption. However, it is possible to remove images or pictures used by The Choice or replace them with your own.

- Systematic and/or complete republication of the articles and content available on The Choice is prohibited.

- Republishing The Choice articles on a site whose access is entirely available by payment or by subscription is prohibited.

- For websites where access to digital content is restricted by a paywall, republication of The Choice articles, in their entirety, must be on the open access portion of those sites.

- The Choice reserves the right to enter into separate written agreements for the republication of its articles, under the non-exclusive Creative Commons licenses and with the permission of the authors. Please contact The Choice if you are interested at contact@the-choice.org.

Individual cases

Extracts: It is recommended that after republishing the first few lines or a paragraph of an article, you indicate "The entire article is available on ESCP’s media, The Choice" with a link to the article.

Citations: Citations of articles written by authors from The Choice should include a link to the URL of the authors’ article.

Translations: Translations may be considered modifications under The Choice's Creative Commons license, therefore these are not permitted without the approval of the article's author.

Modifications: Modifications are not permitted under the Creative Commons license of The Choice. However, authors may be contacted for authorization, prior to any publication, where a modification is planned. Without express consent, The Choice is not bound by any changes made to its content when republished.

Authorized connections / copyright assignment forms: Their use is not necessary as long as the republishing rules of this article are respected.

Print: The Choice articles can be republished according to the rules mentioned above, without the need to include the view counter and links in a printed version.

If you choose this option, please send an image of the republished article to The Choice team so that the author can review it.

Podcasts and videos: Videos and podcasts whose copyrights belong to The Choice are also under a Creative Commons license. Therefore, the same republishing rules apply to them.