Significant changes to the way we learn, work and approach our careers have transformed the learning sector into one of the world’s most promising industries – particularly in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. We examine the future of learning.

It’s fair to say that approaches and opportunities surrounding learning have changed dramatically over the course of the last few decades. Improved access to higher education, more flexible attitudes to careers, flexible work schedules and digitalisation, for example, have contributed to the immense changes experienced by this growing sector.

So, what exactly do we mean when we discuss learning in today’s context?

The idea of continuous learning is not a new concept. However, the concept of learning as a distinct activity, different from acquiring skills on the job or via one’s personal experience, likely is, at least with regards to its magnitude and importance.

Professor Andreas Kaplan, Dean of ESCP Business School in Paris, argues: “Today, we’re still prone to following the classic three-step model: early-life education, first degree or second degree, and then a career and retirement.

In most universities and business schools, the continuous education department is often seen as an add-on, and it’s not fully integrated into the rest of the pathway.

But with the rise of artificial intelligence, automation, and corresponding upskilling that early-life degree will most likely no longer suffice for the whole of a career.”

Continuous learning: a modern invention?

To fully understand current and future trends in the continuous learning sector, let’s take a closer look at its historical and cultural background. The earliest proponents of continuous learning focused on literacy and numeracy among populations with little to no opportunity of attending school.

In this vein, extracurricular learning has long been an important part of Scandinavian society, with ‘folkbildning’ (community learning) popular since the mid-1800s in Sweden and Denmark.

In succeeding years, as access to trades and careers other than those practised by older members of the family grew, lifelong learners became concerned with improving employability and diversifying skill sets.

Founded in 1969, the Open University, the worldwide first institution that augmented correspondence learning through mail and TV, with short residential courses and supporting classes at different physical locations, is the largest academic institution in the UK, with the vast majority of its undergraduates studying off-campus. Its lengthy list of experts and guest speakers remains a huge draw for potential applicants, particularly for those seeking to pursue traditional academic ways of learning.

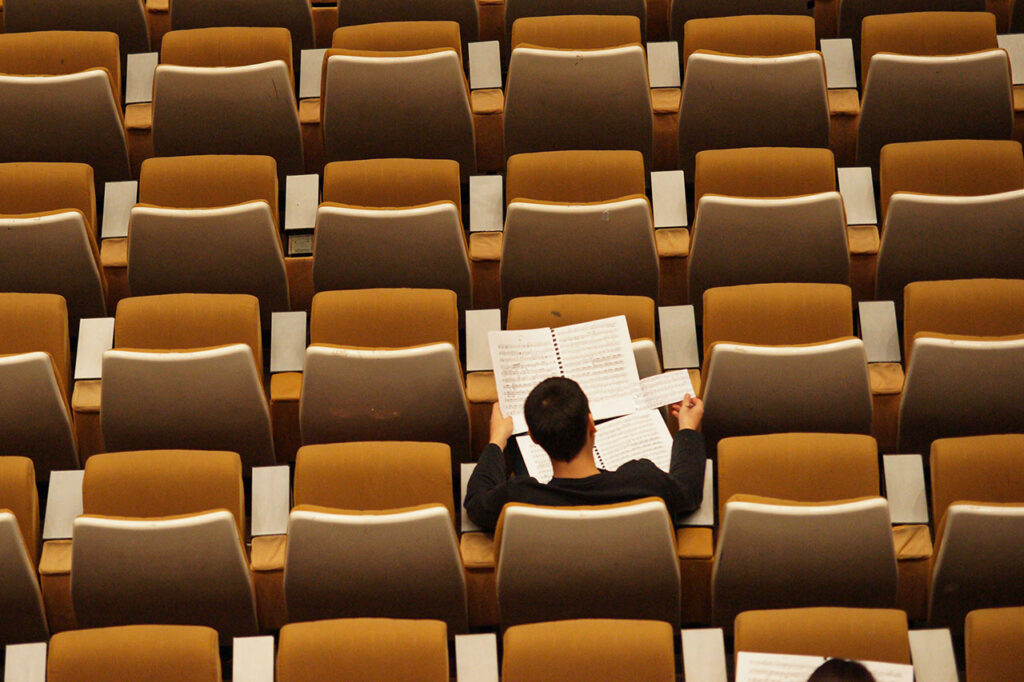

Today, modern lifelong learners are more likely to pursue their goals alone. But while previous generations were concerned with improving employability or developing more advanced technical knowledge, the modern concept of ‘slashing’ has led to workers looking to diversify their skill sets, either for work or for pleasure.

Today’s continuous learning sector offers everything from beginners’ guides to coding, graphic design and launching a business to disruptive approaches to more traditional extracurricular activities, such as modern languages or learning an instrument.

Continuous learning: barriers and opportunities

Of course, it’s unrealistic to assume that the search for better or alternative employment isn’t one of the largest drivers for people pursuing lifelong learning. Kaplan remarks wryly: “We all pursue education or training to, ultimately, obtain a job.”

A recent study by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in collaboration with the OECD highlights the importance of upskilling in the coming years, also highlighted in Dean Kaplan’s recent book publication: Higher Education at the Crossroads of Disruption: The University of the 21st Century.

“Rapid and deep changes brought about by technological development, demographics, globalisation and climate change… are affecting the composition of employment, the nature of the tasks carried out at work and the skills required in the labour market. Skills development can help turn these challenges into opportunities.”

Unsurprisingly, the Covid-19 pandemic saw record numbers of people seeking to diversify their skill sets, apply for new roles or change careers altogether – a trend some employers have hastened to respond to.

Tech giant Google launched a series of six-month training programmes for project managers and data scientists during the pandemic, promising to consider successful participants for standard roles usually only accessible to graduates.

For many, six months of intense study from home, with all of the associated savings and flexibility that distance learning affords, seems an obvious solution when compared with four years’ or more of undergraduate or postgraduate study.

Other leading businesses, such as Orange, Danone and Kering, have begun working alongside startups specialised in upskilling as part of a wider strategy to attract and retain talent.

Sounds like a win-win for both employees and employers, right? Kaplan isn’t so sanguine:

Everybody agrees that lifelong learning is important, but is it really a priority? Employers need to make sure they’re allowing their employees to fully concentrate on their training.

The future of continuous learning

With over 85% of jobs in 2030 yet to exist according to a 2017 study by DELL, it might seem incumbent upon today’s employees to reconsider their approach to learning. The ILO found that jobs most likely to be outsourced include those “with a high routine content”. For Kaplan, artificial intelligence is both a blessing and a curse:

People working in certain sectors will lose out to automation in coming years, which will require them to upskill or change roles. However, artificial intelligence is also disrupting ways of learning. But in the educational sector, artificial intelligence and new tech solutions are offering learning approaches and environments that can be adapted to every learner, regardless of their budget, prior experience, location or family situation.

A very positive trend, and one that’s allowing more people to access training and information from top-tier institutions and experts. This independent approach to learning seems to be reflective of an attitude that’s increasingly sought after in the workplace. The ILO notes that jobs requiring high socio-cognitive or leadership skills are having a growing impact on the state of the workplace. Kaplan agrees:

“In today’s environment and particularly given the rise of work from home, employers are seeking people with leadership skills. The question is, will these employers come to see that the standards and content of alternative learning environments is more and more comparable to those of classic institutions?”

In short, there’s never been a better time to become a lifelong learner.