Governed by Just-in-Time principles, the logistics industry currently mobilizes tens of millions of workers in a variety of categories including truckers, tanker drivers, dockers, material handlers, warehouse workers, etc. They constitute the backbone of global supply chains, enabling smooth connections from manufacturing sites to logistics nodes, and from these nodes to the consumption markets. Logistics workers make goods available at the right places, to the right customer, “just-in-time”. Choke Points: Logistics Workers Disrupting the Global Supply Chain offers a close look at how workers protest, react, and wield their “positional power” in different choke points to resist poor working conditions. Social unrests have the power to disrupt whole supply chains.

Social unsustainability in the logistics industry

Traditionally, the logistics industry has been viewed as an industry of efficiency, where labour is treated as an input-resource used to optimize operations. However, by considering logistics workers as human-beings instead of input variables, the book reveals the ugly truth about the poor and unsecure working conditions in this industry. Poverty-level wages, temporary employment as the new norm, lack of employer-provided health insurance, and other exploitative conditions characterize the logistics working environment. Their work is squeezed by constant pressures from tightened management-by-stress and technology-based forms of labour control. In addition, the influence of neo-liberalism on the logistics sectors in this age of globalization has further marginalized workers and worsened their living and working conditions.

Workers’ resistance against social unsustainability

The book presents workers’ resistance against deregulations, precarious work, and threats of being replaced by new automation waves (especially in ports and warehouses) that transform current employment settings in the logistics industry. Each chapter takes the reader to different logistics choke points around the globe. While the concept of choke point commonly refers to a concrete and well-defined spatial venue, such as ports, warehouses or cranes in docks, in this book choke point means any space where logistics workers actively take actions to demonstrate their resistance and solidarity. Their positional power can take the form of traditional union organizing strategies, or original grassroots and bottom-up protests to disrupt the physical flow in the supply chains.

“The book reveals the innate global sickness of the industry reflected in exploitative working conditions, waves of neo-liberalism and invisible-but-real threats from automation and technologies that replace and marginalize workers”

Why do workers’ disruptive actions matter for business?

- First, because workers’ disruptive actions are costly. The book documents a variety of workers’ collective actions lasting from a few hours of picketing to weeks of strikes. These disrupt the goods movements and hurt the economic performance of logistics companies. For example, the 2012 strike by Los Angeles port clerks cost $1 billion dollars in unprocessed cargo per day.

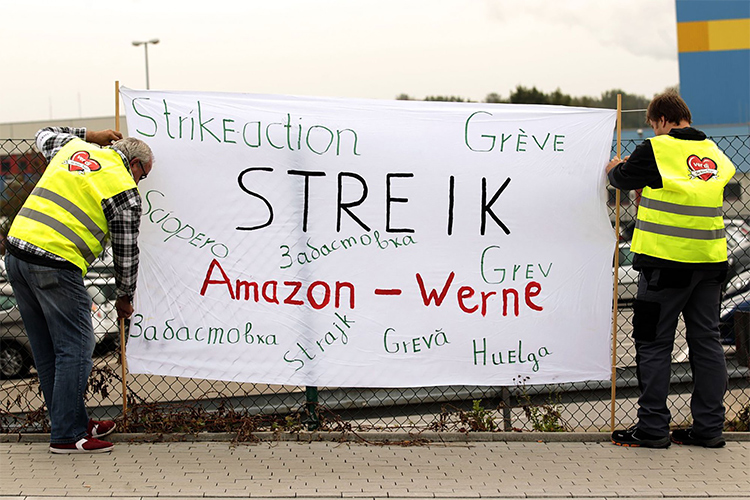

- Second, because the disruption may be much more unmanageable for the firms since workers’ disruptive actions, nowadays, are not isolated in one single place but coordinated with each other. For instance, Polish workers did “the choking” in the Amazon Poznan warehouses through organized slowdowns. These workers did not do “the choking” in isolation, but rather in support of and in coordination with Amazon workers’ strikes in Germany. This collaborative series of disruptions undertaken by workers across borders wrecked Amazon’s strategy of shifting customer’s orders to locally adjacent warehouses in order to undermine the strike of German workers.

- Last but not least, because workers’ disruptive actions remind the firms of the need to take action to address issues of social unsustainability in the logistics industry. The book reveals the innate global sickness of the industry reflected in exploitative working conditions, waves of neo-liberalism and invisible-but-real threats from automation and technologies that replace and marginalize workers. Taking the lens of the Triple Bottom Line for sustainability management, workers’ disruptive actions should not be considered a detrimental phenomenon to the economic pillar but a signal of poor social sustainability management. Improving social sustainability in the logistics industry will reduce economic risks caused by social unrest. Failure to do so will inevitably lead to amplify labour strike waves because workers will increasingly voice their suffering. Therefore, the ultimate message is that global supply chains should be managed to ensure that such workers are afforded decent work.

Tra-My T. Le is a PhD candidate at ESCP. Her research focuses on social sustainability in global supply chains. She is currently studying how organisational decoupling affects field-level workers and the mismatch between macro-level institutions on social sustainability and local institutional arrangements. Before starting her PhD, she worked on labour issues in developing countries as part of her employment at the International Labour Organisation.

Valentina Carbone is a professor of sustainability and supply chain management, and the scientific co-director of the Circular Economy & Sustainable Business Models chair. She has conducted research with public sector bodies such as the European Commission or the French Ministry for Sustainable Development, and her recent work deals with sustainable supply chain management, the sharing economy, and circular economy transition.

This post gives the views of its authors, not the position of ESCP Business School.