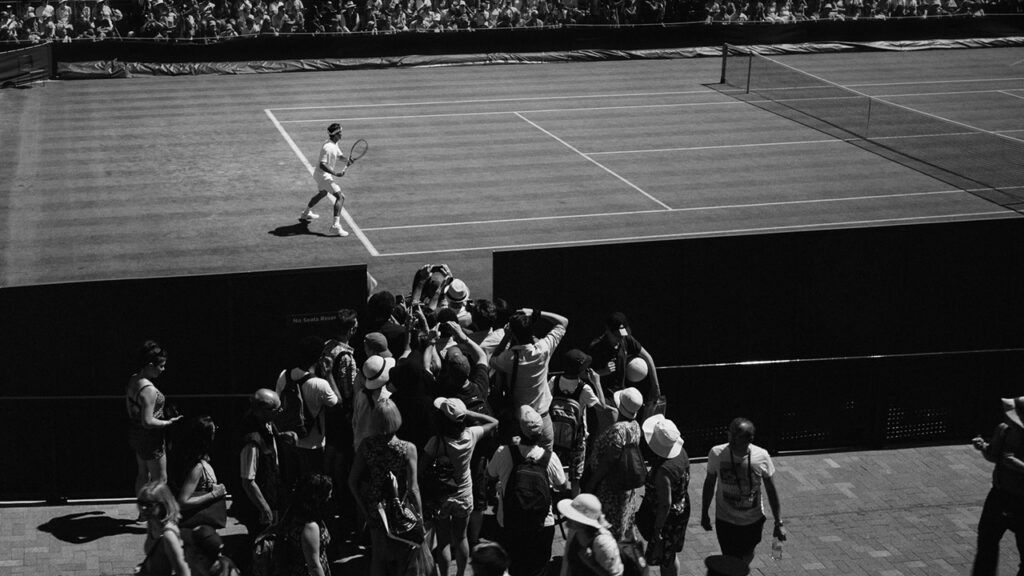

When Djokovic, Nadal, and Federer arrive on the court each has come with an objective in mind. One wants to take back his spot, one wants to defend his title, and one hopes to consolidate his legend by winning as much as possible. But is this obsession with results really the only thing that makes them play so well, for so many years? Let’s take a look at the case of Agassi.

In 1992, at the age of 22, André Agassi wins Wimbledon for the first time. This is what he had been training for from an extremely young age, hitting 2,500 balls per day by the age of 7. For a short moment, brandishing his trophy above his head, he was proud and satisfied. He imagined that he had made it.

But then came the comedown, as quickly as he went up. “I don’t feel that Wimbledon has changed me. I feel, in fact, as if I’ve been let in on a dirty little secret: winning changes nothing,” he writes in his autobiography, Open.

We repeat over and over again that success requires two things: choosing clear and ambitious objectives, and persevering, no matter the cost. You must aim high and never give up.

If that is the best way to succeed in life, a fundamental question pops up: how should you choose and set such objectives? What should you choose as your aspiration, what is something that you want to such an extent that you’ll keep going until you achieve it? Because if perseverance is the key to success, it’s important to choose an objective that will seem just as desirable in a year, as in ten, twenty, or thirty, and that will fill you with lasting happiness and satisfaction when you have achieved it. But how can we know today what will make us happy tomorrow? How can we know if the goal we set today may not end up as an obstacle rather than a driver? How can we know if it will make us feel fulfilled or keep us stuck working towards a goal that, some years later, perhaps no longer corresponds to us, seems absurd or has transformed into a blinding obsession?

We treat our future selves as though they were our children, spending most of the hours of most of our days constructing tomorrows that we hope will make them happy.

Daniel Gilbert, psychologist and Harvard University professor

Making choices precisely means looking towards the future

In Stumbling on Happiness, psychologist and Harvard University professor Daniel Gilbert explains why we are terrible at predicting what will make us happy in the future. “We treat our future selves as though they were our children, spending most of the hours of most of our days constructing tomorrows that we hope will make them happy.” Then the tomorrows arrive, and so does the disappointment.

“How can they [our future selves] be disappointed when we accomplish our coveted goals, and why are they so damned giddy when they end up in precisely the spot that we worked so hard to steer them clear of? Is there something wrong with them? Or is there something wrong with us?” writes Gilbert in his book.

Making choices precisely means looking towards the future, choosing today for the person we will be tomorrow. We go to school, save money, build career strategies, work hard, set income objectives, get married, have children, and do plenty of other things besides, imagining that this will make us happy.

We think we know ourselves and understand what the person that we will be later will need. And we often get it wrong.

Why we overestimate the impact of certain events on our future happiness

According to the Harvard professor, drawing on his own research and that of hundreds of researchers before him, our brain’s ability to imagine the future is actually just as limited as its ability to predict which one it will prefer, among all the possible choices.

One likely reason that explains why we get our forecasts wrong comes from our tendency to overestimate the impact that certain events will have on our future happiness: we imagine that we will finally be happy when we win a certain championship, buy a big house with a pool, become the director of this or that, have 2.5 children, enjoy more time to spend on our hobbies, when our body is sexier, and holidays more glamorous, etc. But this is not the case.

Positive psychology expert Tal Ben Shahar created the term “arrival fallacy” to explain the emptiness created by achieving certain accomplishments. According to him, the arrival fallacy is the idea that we will be lastingly happy when we have attained a specific goal.

This is what he himself experienced after achieving victory at a tournament that he had dreamed of winning as a young squash champion: the happiness and pride of success were quickly replaced by emptiness and, once again, pressure. Exactly what he thought he would be able to escape by winning the title that he had trained so hard for.

In a 1998 study, Gilbert came to the same conclusion. Professors who had been awarded or denied tenure over the past five years were asked to evaluate their current level of happiness.

“For most of them, getting tenure is a sort of Holy Grail: it represents status and financial stability,” explains Gilbert, implying that tenured participants should theoretically be happier than their unlucky colleagues.

Well, no: happiness levels reported by participants were approximately the same for everyone, whether awarded the coveted position or not. However, when each was previously asked to estimate how much happiness this accomplishment would give them, they all significantly overestimated it, both in terms of intensity and longevity, wrongly imagining that the satisfaction of such an achievement would not only be more intense but also that it would last longer.

When it comes time to set our objectives, the problem is not so much our lack of willingness but rather our lack of lucidity…

The problem, according to Gilbert, is that these durability forecasts are precisely what we use to plan our lives and choose our objectives. “People invest in monogamous relationships, stick to sensible diets, pay for vaccinations, raise children, invest in stocks, and eschew narcotics because they recognise that maximising their happiness requires that they consider not only how an event will make them feel at first but, more importantly, how long those feelings can be expected to endure.”

In other words, when we want something, we can provide ourselves with the means to do so. The problem is that what we are pursuing may be the wrong quarry. In even simpler terms, when it comes time to set our objectives, the problem is not so much our lack of willingness but rather our lack of lucidity…

So how can we set “good” objectives?

Well, by choosing objectives that will be gratifying to pursue in and of themselves, whether you achieve certain results or not. By choosing options that do not require us to mortgage our present in hope of a better future, which we believe will start once we have finally achieved our goal.

In other words, by choosing studies, a career, or a project at least as much for what they will bring us in the present as what we expect they will in the future. Because if winning Wimbledon or Roland Garros will not make you lastingly happier, you may as well draw satisfaction from training and playing. Or at least find a certain meaning in it.

And that was Agassi’s very problem. “I hate tennis, and always have,” he writes multiple times in his autobiography. Tennis was not his choice, but rather his father’s, who forced him to play from an extremely young age. This is why for many years, the young Agassi was unhappy with his life — and he showed his frustration the only ways he could, with colourful sneakers, denim shorts and an explosive temper, even in his moments of glory.

And then one day, when he had hit rock bottom and was getting ready to withdraw from the tennis circuit (losing all his games, no longer in the top 100, doing drugs, and going through a divorce), he chose to continue.

And he chose tennis. Because deep down, he knew he could do better. “I hated tennis more than ever. But I hated myself more. I said to myself, you hate tennis, so what? (…) To do what you hate, but doing it well and with drive, maybe that’s the goal,” he describes in his memoirs when revisiting this episode in 1997.

From that point on, his approach and behaviour changed. He slowly climbed back up the hill, participating in back-to-back tournaments. And he ended up winning the French Open in 1999, at the age of 29, five years after his Wimbledon victory. But this time, winning tasted different.

“I lift my arms to the sky and my racquet falls to the ground. I cry. I put my head in my hands. I am terrified to see how good it feels. Winning is not meant to feel so good. Winning is not meant to be so important. But it is. I can’t hold myself back, I am crazy with joy and gratitude (…). I walk off the court, blowing kisses in all directions, something that comes straight from the heart, my way of expressing the gratitude rising in me, an emotion that seems to be at the source of all others. I promise that from now on, that’s what I’ll do: whether I win or lose, I will blow kisses to every corner of the world, to thank everyone,” he writes in his biography.

Tennis is no longer his burden but rather his choice, so he starts to like it. And winning is no longer the sole objective of his efforts: it is a reward and a privilege.

Following his victory at Roland Garros, Agassi was a finalist at Wimbledon (losing the title to Pete Sampras), and then won the US Open shortly after, ending up as the world no. 1. That same year, he started his relationship with Steffi Graff, to who he is still married.

He continued playing until he was one of the oldest players on the circuit, finally retiring at 36 due to back problems.

What’s the point of learning to play the lyre if you’re going to die?” asked the prisoner sharing a cell with Socrates, shortly before his execution. “The point is playing the lyre before I die,” replied the philosopher.

Sometimes, joy is the right choice. Nadal, Federer, and Djokovic must surely know something about that.

This article was first published on Medium.