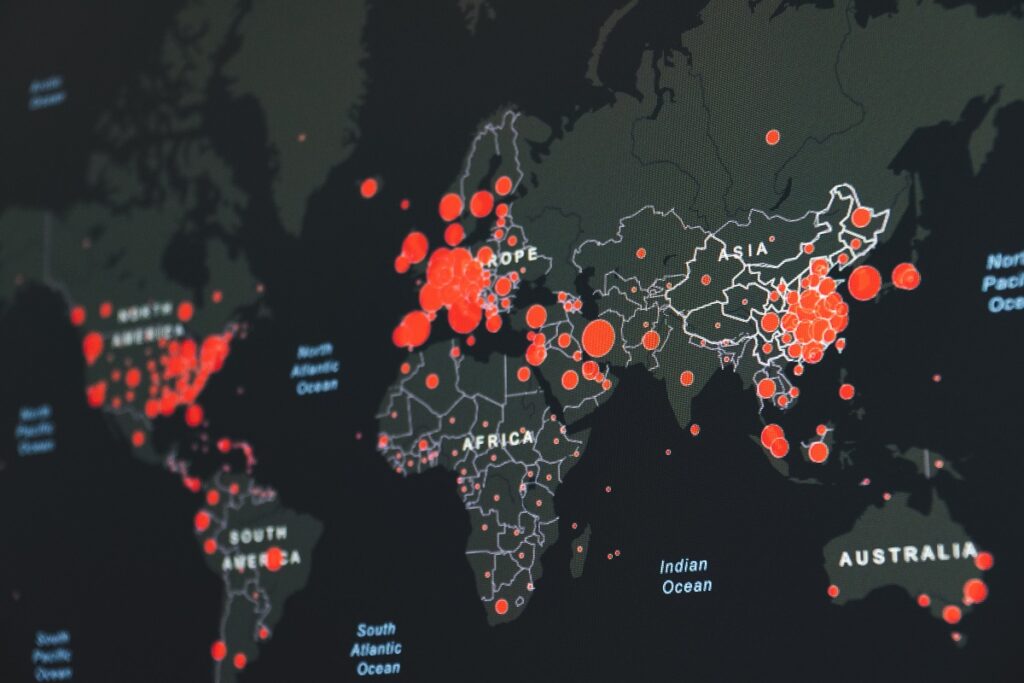

Since the first lockdown, Elias Orphelin, a 22-year-old student completing the final year of his Master in Management degree at ESCP, has made it his mission to inform the public about the coronavirus epidemic in France. How? By compiling epidemiological data in the form of graphs posted on his Twitter account and developing a tool to calculate the risk of coming into contact with an infected individual – His work even caught the attention of Santé Publique France, the French National Health Agency.

On Twitter, you use graphs to provide almost daily updates on the trajectory of the coronavirus pandemic. What made you take on this challenge?

I’ve had a thing for figures since middle school, when I understood that they can tell us many things. Before the pandemic, I was already making a lot of statistical calculations with graphs: about football scores, politics, the economy etc. And in my apprenticeship training at Siemens, I do a lot of “Business Intelligence”.

Among other things, this involves displaying data graphically to help the company with decision-making. Since it’s something that I know how to do and enjoy doing, early on in the pandemic when I was wondering how I could “contribute to the collective effort”, it occurred to me that this skill might be useful for a wide audience.

How did you get started on a practical level?

The very first time I shared a graph, it was in mid-March 2020, at the beginning of the first lockdown. At that time, each regional health agency (ARS) was publishing its own reports and the data was not at all structured like it is today. So you had to go hunting around for numbers, since the numbers for the region I live in, Île-de-France, as well as other regions would be missing at times…I had all the regional health agencies in my favourites on my browser (laughs).

How much time does the research and compilation require?

I’d say 2 or 3 hours a day currently, on average. Even if the data is now more structured on the Santé Publique France web page, it doesn’t necessarily take less time today. At the beginning, we only had the number of cases of infections and the number of deaths. Now, in order to get a 360-degree view of the epidemic, we need to look at the number of cases of infections, the number of tests, the number of hospital admissions and discharges, the number of patients in intensive care etc. It was already multi-factorial before, but we didn’t have access to all this data.

At the beginning, it made me laugh when people would say, “you’re doing what the government isn’t.”

Out of all these indicators, which one is the most meaningful for anticipating the trajectory of the epidemic in your opinion?

The one I follow the most is hospital admissions. That seems to be the most significant to me since it’s an indicator that occurs fairly early in the infection phase and is more reliable than the number of infections indicator (which depends primarily on the number of tests). In early September, the number of hospital admissions was increasing by 30% to 40% per week, but at a very low level. So, in absolute value, it wasn’t increasing that much, but if we looked closely, it formed the beginning of an exponential curve. That’s what makes the problem so challenging: it’s hard to grasp the speed at which the virus spreads. In a matter of days, there are twice as many patients in the hospital. So they get overwhelmed and take urgent action. But in recent weeks, we’ve been discussing another indicator that allows them to save precious days.

Which indicator is that?

The concentration of SARS-Cov2 in wastewater. If we find more of the virus in our sewage, we can see that the virus is circulating in the population of a certain city or neighbourhood, even before the onset of symptoms. Today, this is used very locally. For example, fire departments in Marseille carry out their own analyses. There is a network of researchers working on this technique, but it takes time. In late November, I wrote to the Minister for Research, Frédérique Vidal to ask her to publish this information as open data. I’m sure that if researchers like Guillaume Rozier or Germain Forestier had access to this data, they would be able to use it to perform analyses and develop tools to anticipate the trajectory of the epidemic. The minister’s reply was that it’s a bit complicated for now.

There are days when you don’t feel like looking at how many people have died in France.

You were also behind the idea for a tool to calculate the risk of coming into contact with an infected individual, which can be found on the CovidTracker site.

It was Guillaume Rozier, an engineer, who created the CovidTracker website. A month and a half ago, I sent him a message suggesting that we work together on a tool to calculate the risk of coming across an infected individual. It worked well and we actually also made a model to compare waves and the effects of lockdown measures.

When epidemiologist Catherine Hill was asked about the risk calculator by the website capital.fr, she said that the tool was “not useful since it is based on data that is not the right data.” She points to the fact that the calculator relies on the incidence rate, which only represents the “number of known new cases, meaning positive tests over a week, and not the number of real cases.”

Have you made changes to the calculator?

Yes, we have made updates to get closer to the prevalence rate. The prevalence rate is the number of persons who are ill at a given time (this data is unknown by definition), so it is a higher rate than the incidence rate, which is measured by tests. Since we know that the incidence rate may underestimate circulation of the virus by a factor of two or three, in the calculator on the CovidTracker site, when someone chooses their department, they will see three results: the incidence rate, the corrected rate by multiplying by two, and the corrected rate by multiplying by three. However, we didn’t want to impose the multiplication by two or three times, since we know that the incidence rate is already overestimated since someone who tests positive knows they are ill and will stay home in principle. It’s a phenomenon that offsets “under-testing”.

If people are consulting epidemiological data on your Twitter account or CovidTracker, could we say that it may be due to the fact that there has been a lack of this type of communication by the government?

It’s only recently that graphs have been included in the addresses given by the President and Prime Minister. At the beginning, it made me laugh when people would say, “you’re doing what the government isn’t.” When they were still telling me that in December, one year after the beginning of the pandemic, it made me laugh a bit less. But the authorities have become more aware of this and in the government’s new “Tous AntiCovid” (All Anti-Covid) application, key data is now available.

Do you expect to keep making graphs for a long time?

I hope not!

And what motivates you to devote so much time to this on a volunteer basis?

There are days when you don’t feel like looking at how many people have died in France. But you do it anyway and then you get 15 messages from people telling you: “the lockdown is really hard, but your charts help me understand the situation.” And then you feel like you’re doing something useful. If this is how I can do my part, then I should keep doing it.

This interview first appeared in French in the ESCP alumni magazine.